The love-hate relationship between science, economics and policy

Our ancestors outwitted us in several ways. They could anticipate the future earlier than us; they could comprehend human behaviour better than us; they could frame policies sharper than us. From Rishi Vyasa’s Veda to Kautilya’s Arthashashtra, the repository of ancient knowledge continues to act as a guiding principle in the contemporary world too, for human advancement.

However, this intellect came along with an unexpected baggage consisting of unintended consequences.

Superstitions, for instance, shared a bilateral relationship with science and policy. Fear was used as a central theme to instil values, mould behaviours, inculcate habits, avert mishaps and shape cultures backed by both rational and empirical thinking. Such beliefs were then, institutionalised by cults and cultural groups with the help of policies (religions) and processes (rituals) at an individual level to achieve ‘status quo’ and a sense of ‘control’.

Needless to say, such practices which may have been introduced to bring positive change, had unfavourable ramifications.

Let’s understand this corollary with an example — menstruation.

It remains a provocative topic in most of the world even today, thanks to the countless taboos and superstitions that make this natural phenomenon so malevolent.

In India, particularly, the effects are experienced on a larger scale owing to the lower education levels among girls, cultural norms and religious sentiments shared by societies and most importantly, the politics behind appeasement of the vote banks. From the remotest villages to the most urbanised cities, menstrual shame is an indomitable curse, which has ingeniously managed to escape the political narrative till date.

In this direction, socially applauded movies such as Padman and Toilet — Ek Prem Katha made few important points, to me personally. First, the male protagonist takes up the mantle of women’s health and hygiene rather than the women themselves. Second, the conventional protection method — cloth was staunchly discredited as unhygienic, hazardous and regressive way of living. Infectious diseases were attributed to the widespread use of cloth in absence of ‘better’ avenues, especially in rural India.

If Bollywood can muster the courage to address this highly sensitive menstrual, sanitation subject in India, then why can’t parliamentarians? Or is this bold move actually powered by these parliamentarians?

Once again, the West triumphed over the East.

With the introduction of technologically advanced, scientifically proven, commercially viable and convenience friendly sanitary napkins, India’s women were finally set ‘free’ by ‘progressive’ solutions invented in the West.

This was followed by nationwide lobby efforts to create a new market. Surveys, statistics, case studies, documentaries were used extensively to influence the new customer.

“Incidents of vaginitis and urinary tract infections were 2x among women who used cloth as compared to others using sanitary pads, according to a 2015 study among 486 women in Odisha.”

And, just like that, the West gained market power by controlling the demand — supply equation of the INR 25.02 billion feminine hygiene products market.

“Whisper (P&G) held the largest market share (51.42%), followed by Stayfree (J&J) and Kotex (Kimberly-Clark) in 2018 according to Feminine Hygiene Products Market in India 2019.”

Hey, but what happens to the menstruation related taboos and superstitions?

Well, these issues are best left as a corporate citizenship or CSR campaign. It not only makes an engaging YouTube advertisement but also earns goodwill to be messiah of the feeble Indian women.

Hey, but what happens to the menstruation related taboos and superstitionsAnd just when, the battle against menstrual hygiene was won, a new war emerged from the dumps — literally. The highly commercialised progressive solutions for women, turned out to be regressive for the environment. Disposal of sanitary napkins — a non-biodegradable waste — is posing to be a serious challenge for governments, municipalities and environment.?

“In India alone, 12 billion pads are produced and disposed of annually where a single pad could take upto 800 years to decompose.”

Didn’t the West think of the implications of such ‘progressive’ solutions? Can nothing be done to reverse this impact?

Of course! The West has now turned to reusable / washable / sustainable solution — cloth sanitary pads.

But isn’t this a tad hypocritical? Statistics revealed that cloth pads were responsible for poor menstruation hygiene among women. Perhaps, it’s the composition or design of the cloth that is making the difference now?

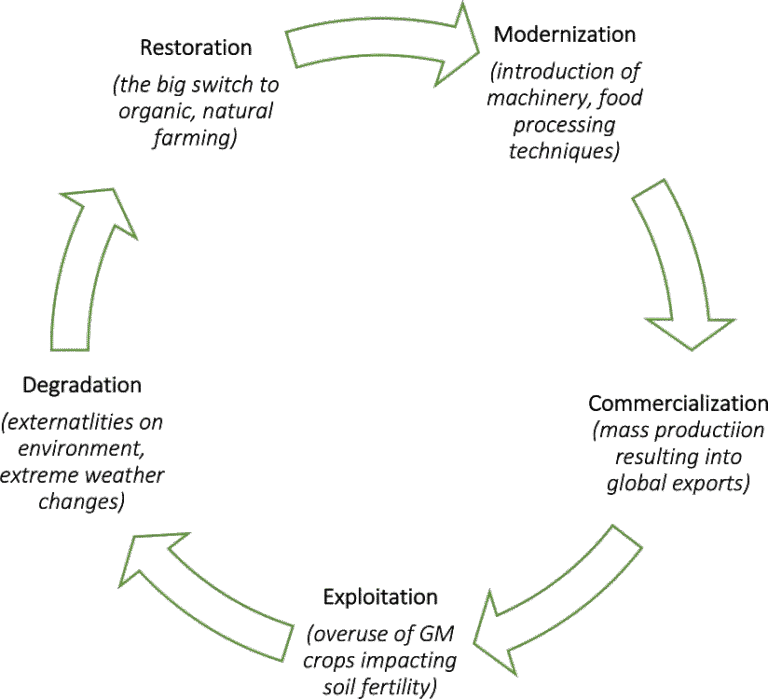

Turns out that the modest cloth wasn’t the culprit after all. Information asymmetry was. In ancient times, it led to superstitions while in the contemporary world, it led to environmental degradation — the unintended consequences created by the entangled triangle of science, economics and policy.

The science behind poor menstrual health, the economics of feminine hygiene market and the policymaking to influence beliefs and behaviours of menstruating women have found ourselves in the same spot as we were decades ago. As the world realises the negative implications posed by ‘progressive’ technologies on the environment, ancient wisdom once again prevails. Cloth sanitary pads — in all sizes, colours, shapes — are all set to make a comeback in the USD 521.5 million Indian market.